Velut Luna

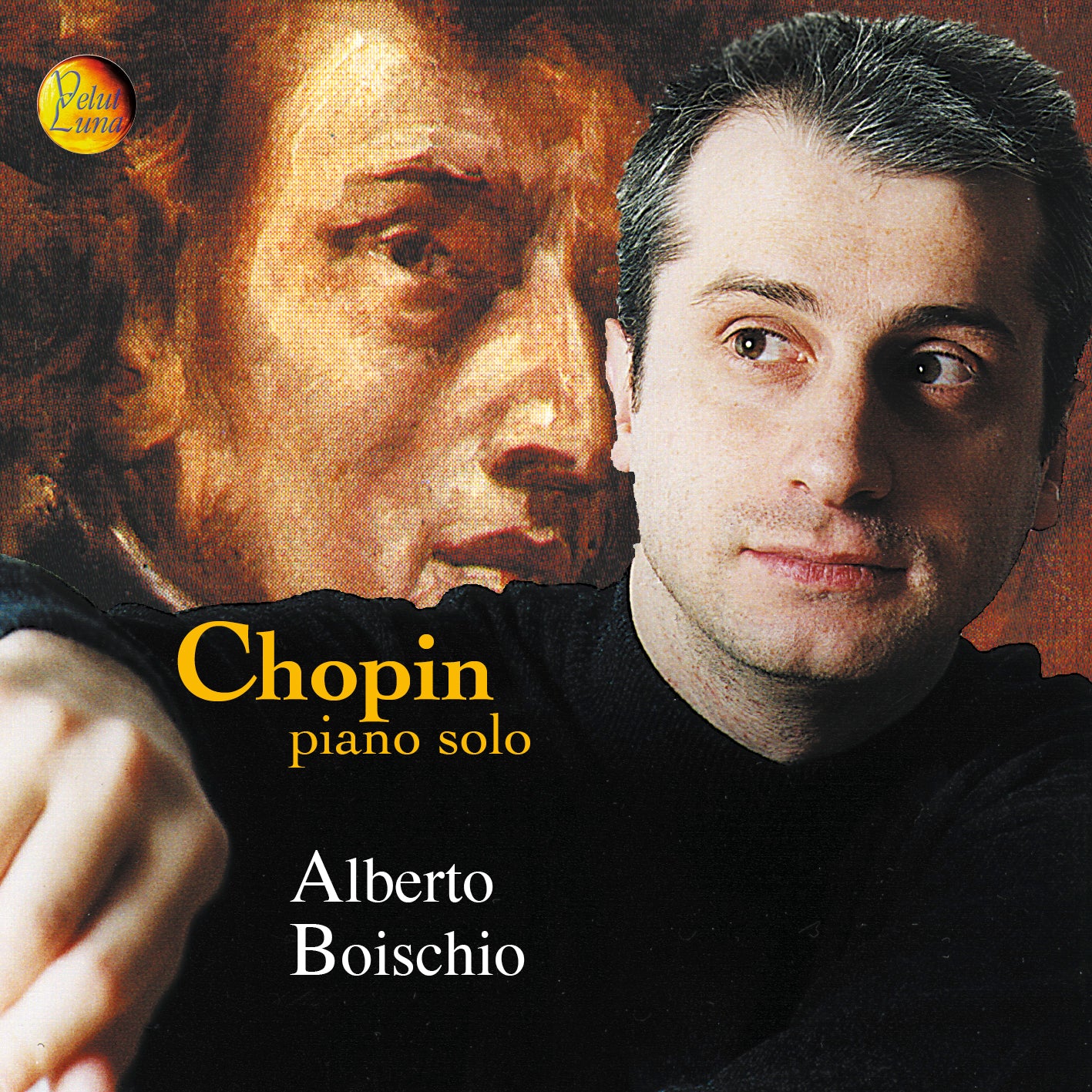

CHOPIN PIANO SOLO - BOISCHIO

CHOPIN PIANO SOLO - BOISCHIO

Genere musicale: Classica

Disponibile

Impossibile caricare la disponibilità di ritiro

CHOPIN PIANO SOLO (CVLD216)

Esecutore: Alberto Boischio

Tracce

1) Ballata in sol min. op. 23, N.1 (1831) 9’23”

2) Mazurka in sol min. op. 67, N.2 (1849) 2’09”

3) Mazurka in la min. op. 67, N.4 (1846) 3’24”

4) Notturno in fa diesis min. op. 48, N.2 (1842) 7’49”

5) Notturno in do diesis min. / op. postuma (1830) 3’47”

Sonata in si min. op. 58 (1844)

6) - allegro maestoso 9’11”

7) - Scherzo, molto vivace 2’37”

8) - Largo 8’13”

9) - Presto non tanto, agitato 5’14”

Durata totale 51’56

Note

A centocinquant’anni dalla morte c’è ancora qualcosa da scoprire in Chopin? Per quanto riguarda la biografia direi di no: anche le nubi che gravavano sui suoi antenati sono state spazzate via da puntigliose ricerche d’archivio, anche del padre s’è ricostruita interamente la vicenda terrena, e, a meno che non saltino fuori sconosciute memorie, chiuse in archivi di famiglie che a Chopin furono vicine, non sembra che i lati ancora oscuri della sua vita possano essere illuminati. Sui suoi rapporti con i contemporanei, e specialmente con George Sand, s’è indagato a fondo, riportandosi infine, dopo un secolo e più di favole, a ciò che risulta dai documenti. Gli studi critici hanno ancora aperti, a parer mio, tre grandi filoni di indagine: la Tecnica, la Conciliazione di Microcosmo e Macrocosmo, il Sentimento della Patria.

La tecnica rivoluzionaria di Chopin nasce in connessione con una rilevante evoluzione nella costruzione del pianoforte: fra il 1820 e il 1830, circa, lo strumento acquisisce il telaio con placche e barre metalliche di tensione che rinforza il tradizionale telaio in legno, acquisisce corde più grosse e più tese, martelletti più robusti e ricoperti in feltro invece che in pelle, una meccanica più pesante. La tecnica classica, codificata da Muzio Clementi, non permette al pianista di sviluppare tutte le potenzialità sonore del pianoforte romantico, e i tentativi di conservarla adattandola alle mutate caratteristiche dello strumento non hanno successo. Chopin crea invece una tecnica che della tradizione classica respinge alcuni postulati fondamentali (come l’uguaglianza delle dita e l’azione limitata alle dita e alla mano) e che scopre possibilità di tocco prima sconosciute.

Alcuni critici conservatori del tempo di Chopin ritennero ineseguibili gli Studi op.10, che se affrontati con la tecnica di Clementi erano effettivamente ineseguibili. Ma negli Studi op.10 e op.25 viene inventata una tecnica nuova e a larghissimo raggio, che per il pianoforte rappresenta una definitiva acquisizione. Successivamente, nei Tre Nuovi Studi, Chopin affronta, per così dire, la nascita del suono sul pianoforte, cioè il limite che separa il suono e il silenzio, aprendo un campo che verrà esplorato a fondo, cinquant’anni più tardi, dai simbolisti francesi. Ora, sulla tecnica di Chopin, studiata sui testi e sui pianoforti ch’egli ebbe familiari, c’è a parer mio ancor molto da dire.

La forma più complessa creata dalla classicità è la sonata, che nei suoi momenti più tipici riunisce quattro forme diverse: l’allegro bitematico e tripartito, la canzone bitematica, lo scherzo con trio, il rondò. Questa grande forma si erge come baluardo invalicabile di fronte ai compositori che si affacciano sulla scena verso il 1830.

Già Schubert, scomparso nel 1828, viene e sarà considerato per tutto il secolo un maestro delle piccole forme, e i compositori romantici tendono a valersi delle piccole forme e a riprendere e sviluppare, l’una indipendentemente dall’altra, le forme della sonata classica: ad esempio, la ballata di Chopin deriva dall’allegro bitematico e tripartito, lo scherzo di Chopin deriva dallo “scherzo con trio” di Beethoven.

Un altro esempio di sviluppo di una forma tradizionale, quella bitematica, è costituito da alcuni notturni, che ampliano a dimensione e significato poematico la dimensione salottiera di John Field. Chopin affronta anche, e sia pure per eccezione, la grande forma classica; ma come Schumann, egli organizza le piccole forme in cicli, creando il polittico. In questo senso sono da considerare alcuni gruppi di mazurke e di valzer, ma soprattutto i Preludi op.28, nei quali la forma aforistica, la forma monotematica tripartita e la forma di canzone vengono inserite in uno schema complesso e rigidamente strutturato a priori. Molti studi sono stati fatti sui Preludi, anche ultimamente; ma non mi sembra che il “segreto”, che l’enigma di questo capolavoro assoluto sia stato svelato.

Il terzo punto nodale, nella poetica di Chopin, riguarda la sua non-appartenenza alla cultura centroeuropea che aveva dominato il campo della letteratura pianistica durante la classicità. Figlio di una polacca e di un lorenese trasferitosi giovanissimo in Polonia, Chopin parla polacco, si forma culturalmente a Varsavia, ed è il primo compositore che raggiunge una fama internazionale usando sistematicamente stilemi appartenenti alla tradizione musicale del suo popolo che vengono innestati su stilemi della lingua franca, della “koinè” europea.

L’esotico era già apparso da tempo nella musica centroeuropea. Ma per Chopin l’esotico non è un momento del pittoresco: egli non saggia di tanto in tanto l’esotico: egli è l’esotico, e la cultura della sua terra investe le strutture europee trasformandole. Fin dallo Scherzo op.20 una scala musicale caratteristica della Polonia viene messa a confronto con l’armonia europea: ne nasce un accordo che farà discutere i teorici per tutto il secolo.

Negli anni trascorsi a Parigi Chopin tornerà costantemente su questa, possiamo dire, inusitata reazione chimica; e in questo modo, invece di creare l’opera nazionale secondo le intenzioni dei musicisti che avevano simpatizzato con la rivolta di Kosciuszko nel 1794 e con l’insurrezione del 1830 - 31, influenzerà profondamente il corso della musica mitteleuropea fino al decadentismo. E anche qui, malgrado gli sforzi di biografi e critici, qualcosa di oscuro resta.

Che cosa ci porterà il 1999? Qualche novità o un pigro rifiorir di favole?

Piero Rattalino

La registrazione è stata effettuata a Schio nella Chiesa di San Francesco il 24, 25, 26 settembre 1998, utilizzando per la prima volta in Italia la nuova tecnologia ad alta densità digitale 24 bit / 96 Khz.

Production: Velut Luna

Executive producer: Marco Lincetto

Musical producer: Maria Grazia Bambini

Recording & Mastering engineer: Marco Lincetto

Editing engineer: Fabio Framba

Design: l’image

Photo: Ilenco Tracmot

Marketing: Francesco Pesavento

Sales Manager: Moreno Danieli & Patrizia Pagiaro

Press Agent: Emanuela Dalla Valle

World Wide Contacts: Cristiana Dalla Valle

Share

-

Spedizioni prodotti fisici

Spedizioni gratuite in Europa (UE), a partire da 4 articoli - Richiedere quatozione per i costi di spedizione per i paesi non UE

-

Consegna prodotti digitali

La consegna dei prodotti digitali avverrà direttamente sul sito e riceverai anche una email con il link per il download dei file.

-

Scrivi una recensione

Qui sopra puoi scrivere una recensione sul prodotto che hai acquistato, saremo felici di conoscere la tua opinione.